The Basics of Go

Learn the basics of Golang in just one single article

Posted on 09/11/2021

First and foremost, I can't teach this material in Indonesian. So, to understand this article, you should know at least basic of English. Even if you don't, you can always try Google Translate.

Short introduction

Go (usually written as Go, but pronounced as Golang) came around in the year of 2009 by Google. It's a compiled, statically-typed language where unlike Python or Javascript, it directly compiles to machine code and have strict type declaration for variables and functions.

A few things that I like from Go are:

- Very easy to install, and its toolings are available for most text editors, even IDE.

- Very lightweight when compiled to binary (yes, it compiles to a binary format that you can run anywhere)

- Boring code, meaning the code, whoever it is that wrote it, would be easy to read and understand by anyone.

- The standard libraries are not as confusing as Node.js or Rust's.

- Automatic documentation generation for packages.

- Can be easily decoupled, you can put a single packagee and take out another package without having headaches.

- Can embed files into the binary build.

Some things to be acknowledged

Like all programming language, the first thing that you should do is to drop how to do things on any other programming language, but just keep the concept of it.

In Go, most people from Java and PHP might say, "How can this language be good? It doesn't have class keyword, it can't do OOP!". Well, you're wrong. OOP concepts such as inheritance, encapsulations and others don't really rely on the class keyword itself. You can do OOP in Go, but do you really need OOP tho? There are lots and lots of other patterns that you could implement in Go.

If you've seen the formatting of Go, yes, we use the gofmt to lint and format the style of Go codes. And yes, all

of us hate it, because it's opinionated. But hey, we all also love it because of that reason. It provides consistency

across projects.

Some problem surrounding Go programming language when it's compared to other programming languages should be ignored because.. well.. why should we? Language is just a tool for us as a software engineers to use. With that being said, I would like to clarify that Go, might not always be the best language for you to use. It all depends on the project that you're handling, it depends on the problems that you're facing.

With all that, let's Go.

The start of the program

A Go program starts with a package keyword, which usually for the main package, it will be package main.

Then, the main code that will be executed will be inside a function, which then again is called a func main().

So, a basic hello world program in Go would be:

package main

func main() {

println("Hello world")

}And yes, it's func, not function, fun, or fn. And there are a lot of ways to print something out into

the console.

To run the program, save it first into a some file with an extension ending in .go. Then, open your terminal

and type: go run <file_name>.go. To format the file to have it easier to read, you can run go fmt.

To build it into a binary (executable) file, you can run go build <file_name>.go.

About packages

"Package" is a keyword that's most often being misunderstood in Go. To put it simply, package is a collection of Go files within a single folder. By convention, the main entry point for Go program will be called package main. Whereas for other packages, it will be called as the directory name. So that if I happen to have a folder called "controllers" that lives as a subfolder from the main package, it will be named as package controllers. Which shaped this folder structure:

.

├── main.go (package main)

└── controllers

├── index.go (package controllers)

└── users.go (package controllers)

Consider the directory and package structure above. The first question that I had when learning about Go is: how do you actually import a Go file?

Well, you don't. You don't import a file, because this is not a scripting language like Javascript, PHP, or Python. If you

want to import a file, you should import the whole package with the keyword import "<package name>".

If I have some function that I want to import from the controllers/index.go into the main.go file, I would do:

// main.go

package main

import "project/controllers"

func main() {

controllers.SayHello()

}

// controllers/index.go

package controllers

import "fmt"

func SayHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello!")

}Simple, right? It also goes the same for things that are on the controllers/users.go, you just need to import

controllers once.

What about public and private scope in Go?

It's straightforward:

- Anything that would meant to be public scope (a type, function, variable, or constant) should be named with an uppercase

on the first character. Example:

func SayHello(). - Anything that would meant to be a private scope, should do the opposite of public scope. It should be named with a lowercase

on the first character. Example:

func sayHello().

Data types

Go has some built-in data types, which I will only mention some of the important ones:

bool- boolean value being either true or false.string- a string of characters.byte- byte is an alias for uint8 and is equivalent to uint8 in all ways. It is used, by convention, to distinguish byte values from 8-bit unsigned integer values.error- error built-in interface type is the conventional interface for representing an error condition, with the nil value representing no error.int- int is a signed integer type that is at least 32 bits in size. It is a distinct type, however, and not an alias for, say, int32.uint- uint is an unsigned integer type that is at least 32 bits in size. It is a distinct type, however, and not an alias for, say, uint32.

Variables

There are some ways to create a variable in Go:

package main

func main() {

// Oh by the way, this is a comment.

var str string // Declares a variable called str, which holds an empty string

// The declaration above is equivalent to:

var str string = ""

// Why is that? We'll touch that in a minute.

// Meaning this is also possible and correct:

var str string = "Something fishy"

var str = "Something fishy" // The string type will be infered.

// Or a shorthand, which will be mostly used.

str := "Something fishy"

// You can also declare multiple variables at once.

var (

name string = "John"

age int = 30

)

// Or..

var name, age = "John", 30

name, age := "John", 30 // Shorthand declaration.

}Go has something called zero value. Zero value is the default value of a variable. For example, if you declare a string type variable, it will have an empty string ("") as the default value. If you declare an integer type variable, it will have 0 as the default value. And if you declare a boolean type variable, it will have false as the default value.

By default, variables in Go are mutable, meaning you can change the value of it after the declaration. So this is valid:

package main

func main() {

var str = "Something fishy"

str = "Something else"

str = "Oh, I also thought of something else again"

}What if you want it to be immutable? We'll need to use the keyword...

Constant

Unlike variables that are mutable, constants are immutable. You can't change the value of it after its declaration.

package main

const (

pi float64 = 3.14

e float64 = 2.71

)

const NUMBER_OF_LIVES = 9

// Yes, you can declare a constant or even a variable outside a function.

// It's valid and nothing's wrong with it.Array, slices and maps

Array is simple. It's a fixed-size list of elements of the same type.

var people [3]string = [3]string{"John", "Paul", "George"}

// But GoLand, the Go IDE by JetBrains would find that to be redundant,

// so you'll have to remove the [3]string type.

var people = [3]string{"John", "Paul", "George"}

fmt.Println(people[1]) // PaulSlices are like array, but it's a variable-size list of elements of the same type.

var people = []string{"John", "Paul", "George"}

fmt.Println(people[2]) // GeorgeWell, what's the difference between array and slices? Simple. They have different capacity size. If you have an array of string that have a length of 10, you can't add another value on the 10-th index (as Go array starts from 0). But if you have a slice of string that have a length of 10, you can add another value on the 10-th index.

Now, you've talked about add another value to a slice. How do we do that? Use append.

To know the length of an array? Use len. To know the capacity of an array? Use cap.

var people = []string{"John", "Paul", "George"}

people = append(people, "Ringo")

fmt.Println(people) // ["John" "Paul" "George" "Ringo"]

var length = len(people) // 4

var capacity = cap(people) // 6Wait, why the capacity of people is 6? Well, I'm not going to explain this right now. But if you're curious, you can read this article to know more.

Maps is like a Dictionary, Associative Array, Object, or Hash in other languages.

var capitalCities = map[string]string{

"France": "Paris",

"Italy": "Rome",

"Japan": "Tokyo",

}

fmt.Println(capitalCities["Japan"]) // Tokyo

var phoneNumbers = map[string]int{

"John": 123456789,

"Paul": 234567891,

"George": 345678912,

}

fmt.Println(phoneNumbers["George"]) // 345678912Functions

Like all programming languages that ever existed, function acts the same. It has a name, want zero or more arguments, and return a value (void or empty return is also a value). In Go, you can return more than one value to it.

package main

// "fmt" is a standard library.

// Most people use it to format something, as

// it is a formatter package after all.

import "fmt"

// Calculate will take 2 integer arguments and returns

// the sum of them on the first result

// and the difference of them on the second result.

func calculate(a int, b int) (int, int) {

return a + b, a - b

}

// Then we can use it like this:

func main() {

result1, result2 := calculate(10, 5)

fmt.Println(result1, result2)

}Function also take shorthand if the arguments have the same data type.

func calculate(a, b int) int {

return x * y

}Control Flow

Go is pretty much straightforward as you would see and do in C or even other C-family languages.

But please bear in mind, I omit the package main and func main() keyword just for the sake of

keeping the article short. You must use those two keywords if you were to code seriously in Go.

var x int = 10

if x > 5 {

fmt.Println("x is greater than 5")

} else if x < 5 {

fmt.Println("x is less than 5")

} else {

fmt.Println("x is equal to 5")

}

var country string = "Brazil"

switch country {

case "Brazil":

fmt.Println("Brazil is the best country in the world")

case "USA":

fmt.Println("USA is the best country in the world")

default:

fmt.Println("I don't know where is this country")

}

// There is even a fallthrough keyword, so you can do:

var ranks int = 3

switch ranks {

case 3:

fmt.Println("You are a pro")

fallthrough

case 2:

fmt.Println("You are a regular")

fallthrough

case 1:

fmt.Println("You are a newbie")

fallthrough

default:

fmt.Println("You are a legend")

}

// This will print out:

//

// You are a pro

// You are a regular

// You are a newbie

// You are a legendFor loops are also straightforward:

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

// Do something!

fmt.Println(i)

}If you're messing around with slices or maps, you can use the range keyword.

var people = []string{"John", "Paul", "George"}

for index, value := range people {

fmt.Println(index, value)

}

// Output:

// 0 John

// 1 Paul

// 2 George

var phoneNumbers = map[string]int{

"John": 123456789,

"Paul": 234567891,

"George": 345678912,

}

for key, value := range phoneNumbers {

fmt.Println(key, value)

}

// Output:

// John 123456789

// Paul 234567891

// George 345678912In Go, we have no while keyword. The only way to do a while loop is just use for loop.

for i < 10 {

// Do something!

fmt.Println(i)

i++

}We also have an infinite loop!

for {

if x == 5 {

break

}

x++

}Defer

I want to make this a little separate than the control flow section, because this might be new for some people.

Defer means "I'll execute this function (or code, or whatever) later". It literally is. If something is deferred,

it will be executed after the return call, or after the function exits.

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("This is a defer statement")

fmt.Println("This is a normal statement")

}

// Output:

// This is a normal statement

// This is a defer statementYou can also stack a defer statement like so. It follows Last In First Out (LIFO) order.

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("This is a defer statement")

fmt.Println("This is a normal statement")

defer fmt.Println("This is another defer statement")

fmt.Println("This is another normal statement")

}

// Output:

// This is a normal statement

// This is another normal statement

// This is another defer statement

// This is a defer statementPointers

Oh well, I'm not going to explain what a pointer is and how to use it. That will be another article.

But in Go, you can use the & operator to get the address of a variable. This is called a pointer.

And you can get the value of a pointer by using the * operator.

And for C/C++ programmers, there are no pointer aritmethics in Go. If you want to play around with the pointer, use the unsafe package. If you want to know more about why there are no pointer aritmethics in Go, this section is a good read.

Struct

Dear Javascript developers, struct is not equivalent to Object. But for Typescript developer, a struct is kind of equivalent to an interface. Or if you come from Rust, struct is kind of equivalent to a struct.

To declare a struct, you use the type keyword. Let's make a struct called Person.

package main

type Person struct {

Name string

Age int

Alive bool

}Okay, we've created a struct called Person. How can we instantiate it?

func main() {

var person = Person{

Name: "John Doe",

Age: 25,

Alive: true,

}

}What if I want to create a struct within a struct? Of course, you can. You can create a named struct or an anonymous struct.

type School struct {

Name string

// This is using the named or

// predefined struct.

//

// On this one, it accepts array of

// Student struct.

Students []Student

}

type Student struct {

ID int64

Name string

// This is the anonymous struct

Classes []struct {

ID int64

Score int

}

}Okay, that sounds complex. What if you only have a few value that can be put into the struct? Sure, you can put them later.

var school = School{Name: "My School"}

school.Students = append(school.Students, Student{

ID: 1,

Name: "John Doe",

Classes: []struct {

ID int64

Score int

}{

{1, 100},

{2, 90},

},

})

school.ID = 23915Methods

Methods is basically a function of a type with a receiver argument. So initially, you would define a struct first, then make some function from that.

type Person struct {

Name string

}

func (p Person) SayHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello, my name is", p.Name)

}Interface

Interfaces is basically a set of method signatures. You can define an explicit interface of a type, or you can

define an interface with a set of methods. Let's make an interface called Speaker.

type Speaker interface {

SayHello()

SayGoodbye()

}You can make a struct that implements the interface. So, this is kind of what you'd expect when you're asking "oh no, I love OOP, why don't Go has OOP?". Listen here you little brat, OOP doesn't depend on whether the language have a "class" keyword or not. OOP is just a way of thinking about things. Not merely a specific way of doing things.

Okay, let's end that rant. Let's make a struct called Person that implements the Speaker interface.

type Person struct {

Name string

}

func (p Person) SayHello() {

fmt.Println("Hello, my name is", p.Name)

}

func (p Person) SayGoodbye() {

fmt.Println("Goodbye, my name is", p.Name)

}

func main() {

var speaker = Speaker

speaker = Person{Name: "John Doe"}

speaker.SayHello()

speaker.SayGoodbye()

}Interface could be empty. So, you can make an interface that has no methods. This is the equivalent of any (that

means literally a type of anything), and might be useful when you're dealing with things that you don't know.

But is it encouraged to do so? No. You should be careful with interfaces. Go is not a dynamically typed language. So you have to validate the given type of the interface.

func main() {

var i interface{}

i = 42

describe(i)

i = "hello"

describe(i)

}

func describe(i interface{}) {

fmt.Printf("(%v, %T)\n", i, i)

// Output:

// (42, int)

// (hello, string)

}To validate a given type, there are two ways. One, via the type assertion:

var i interface{} = "hello"

s := i.(string)

fmt.Println(s)

s, ok := i.(string)

fmt.Println(s, ok)

f, ok := i.(float64)

fmt.Println(f, ok)Or two, via the type switch:

func do(i interface{}) {

switch v := i.(type) {

case int:

fmt.Printf("Twice %v is %v\n", v, v*2)

case string:

fmt.Printf("%q is %v bytes long\n", v, len(v))

default:

fmt.Printf("I don't know about type %T!\n", v)

}

}

func main() {

do(21)

do("hello")

do(true)

}Error

I want to tell a little story before we go forward. Go's error handling is a bit unique. It's not like C/C++,

where you have to define a custom error type. But it's not like Java, where you have to define a custom exception.

There are no try-catch blocks. And there are no exceptions. But Go has an error type that must be defined explicitly,

which is called error, and means your code will be so verbose. I once had an internal talk on one of the

company that I worked on, and when I explain about why there are error on the function signature and how

verbose your code should be, some PHP and C# developers were confused and immediately don't like the language.

Not long after, I told them, "well yeah, you could just do panic()". And they laughed, "how can a language be so much

like a developers who would just panic whenever they see an error?"

You might not understand that story, but the point is that you should not be scared or hate the language just because its error handling is verbose. After a while, I think being able to handle an error programatically (and with that so much verbose-power) is good, because in Go, errors are just values. You can decorate the error, and find out what was going on and where the error is without trying to read the stack trace.

Here, we're going to use a function from the strconv standard library to convert a string into integer.

package main

import (

"strconv"

"fmt"

)

func main() {

i, err := strconv.Atoi("420")

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

return

}

fmt.Println(i)

}Seems like no problem right, there won't be any error. But what if the input string is not an number, but it's a string of "four two oh". It would fail and won't output a valid integer right? That's the error that you as a developer should handle on your own.

Concurrency

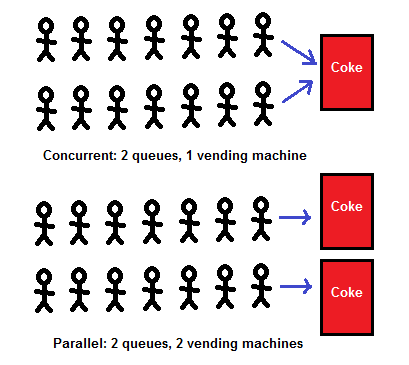

Concurrency might be something that you are familiar with if you're coming from Kotlin or other languages that have coroutines. Concurrency is a way to run multiple tasks simultaneously, maximizing the performance of the multi-core CPU of your computer. In a way, it's different than parallelism, which is a way to run multiple tasks at the same time. I found an image to describe the difference between them that I think would be easy to understand.

Goroutine

In Go, it's super easy to make a function running concurrently. Meaning it won't block the main thread.

Just add a go keyword in front of the function, and you're good to go.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func say(s string) {

for i := 0; i < 5; i++ {

time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println(s)

}

}

func main() {

go say("world")

say("hello")

}Oh anyway, it's called a goroutine.

The output of the say("world") function is not deterministic, meaning it's not guaranteed to be printed

in the same order. But the output of the say("hello") function is deterministic, meaning it's guaranteed to

be printed in the same order.

Confused? Okay, let's make another example that would give you a better understanding of what's deterministic and what's not.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

// Count will count from n to n+5

func count(n int) {

for i := n; i < n+5; i++ {

time.Sleep(500) // Sleep for 500 ms

fmt.Println(i)

}

}

func main() {

go count(0)

go count(8)

// We need something to hold the main thread,

// otherwise the program will exit immediately

fmt.Scanln()

}The output of the code above wouldn't be exacly 0 to 4, then 8 to 13. They might overlap each other in a way that this output would occur.

0

1

8

9

2

3

4

10

11

12

In the real world, goroutines are used to do multiple things at the same time, background work, or anything that would require very fast stuffs. A simple example (well at least, for me) is a captcha bot. If you visit the Teknologi Umum's Telegram group, the first thing that you'd meet is the captcha bot. It does basic captcha validation for each joined user.

But the question now is, how do you handle that if there are multiple users joining at the same time? On a normal code, the captcha bot would just wait for each user to solve the captcha, then move to the next user, right? But is it ideal? What if the second user who joined just gave a spam message? It would be a total chaos.

So, I came up with this flow:

- A user joined the group. The captcha bot will send a captcha to the user.

- The captcha bot calls a function that start a 60 seconds timer for the user to complete the captcha with goroutine.

- If 60 seconds has passed, and the user hasn't solved the captcha, the captcha bot will kick the user.

- Listen to any incoming message by anyone, and if the message was sent by one of the user that needs to solve the captcha, we will validate their input.

- If the user solved the captcha, we will send a message to the user that they have solved the captcha. And remove the user's captcha from the list of active captcha.

It's that simple, but effective. An additional use for the goroutine is to automatically delete the message that was sent by both the user and the bot. The code of the system above is available on Github.

Channel

Let's dive about one more thing before we end this article: Channel.

Channel is a way to communicate between goroutines. To use it, simply make a channel of a type, and then use the channel as usual. Channel is a type that can be used to send and receive values. Let's see the example code so you won't have to bother with all the technical terms.

package main

func giveValue(c chan string, v string) {

// This is how you would send a value

// into a channel.

//

// c is an argument variable (see function signature)

// that holds a channel of string.

// v is also an argument variable, that's

// a type of string.

c <- v

}

func main() {

c := make(chan string)

go giveValue(c, "hello")

go giveValue(c, "world")

// <-c means we receive a value from the channel c

// into the result variable.

//

// Well, you can also do directly fmt.Println(<-c)

// but that would confuse you.

//

// This blocks the main thread until there is a value

// received by the channel.

result := <-c

fmt.Println(result)

result = <-c

fmt.Println(result)

// Output:

// hello

// world

}Where to Go next?

There are more things to be discover. So many things are not covered on this article such as

dealing with the make() and close() built-in functions, buffered channels, select statement,

named function return, Go modules, and so much more.

To dive in much deeper, you can try Go Tour, exploring Go by examples, visiting Awesome Go to see what can you make with Go, or you can start coding some Go programs on your own.